Originally published on June 21, 2019 on Project 40 Collective’s Blog.

The intersection of archives and art has always captivated me. When working with personal narratives of my own diaspora, I find myself contemplating themes of vulnerability and responsibility, along with the reception of the created work both within and outside my community.

When I encountered Zinnia’s work, I became curious about her relationship with archives because of her use of family photos and home videos. Zinnia shares her belief that employing our personal archives is crucial to reclaim narratives that have been predominantly told by others. However, she also emphasizes the importance of retaining authenticity in this process. Her words have ignited contemplation within me, prompting me to explore the potential of archives, particularly their future within the context of the Asian diaspora. It seems Zinnia’s work is guiding us toward uncharted territory.

Read my interview below as Zinnia, one of the 2019 New Generation Photography Award winners, shares her journey into photography, family archives and installation work, as well as her “favourite” video-performance artist.

Could you tell us briefly about your creative journey? When did you see photography and video as a way of expression?

Zinnia: I talk about this in one of my works Seaview, but I found out about a Pakistani photographer named who was very popular on Flickr when it just started, and I was really captivated by his photos and how they showed the beauty of Pakistan which was very different than how I remembered it when I visited. Then I was able to take darkroom classes in high school and decided to apply to the Photography program at Ryerson University. In the beginning I thought I would be a photojournalist because I was interested in photography’s ability to tell stories, often accompanied by text. I still do that now but in a way that is a bit more experimental, and I guess I am usually telling my own stories rather than other people’s.

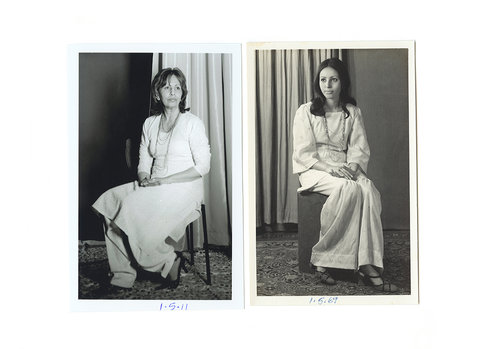

From the photographic series Past and Present to your recent Yours to Discover at the Peel Art Gallery, many of your work handle personal archives, examining intergenerational and cultural identities, histories, and narratives. I’m particularly intrigued by your process of engaging with old photographs and juxtaposing them with contemporary and critical perspectives. When you present these works to the public, how do you navigate the vulnerability that both you and the subjects might experience?

I started doing this very early on. The first photo series I ever made used archival images, and from then on I was encouraged to combine my own images and interact with archives. But it does definitely come with its own weight and I am constantly questioning the use of my own family’s experiences and bodies within my work. I think in each project it’s different and I am constantly looking for new ways to both use and interrupt the archive. With Dear Nani, I found images I know I had to show because they were so unique and exceptional, but I also felt the weight of showing them in a way that explained the nuance and complications of what was happening in the images

With my new project Yours to Discover, I am using my family archive in a way that I could have with any other archive; to explore the newcomer and the tourist experience. But in this case, using my own family’s photos makes me feel like I can take certain liberties as to how I use them, while at the same time I’m also responsible for how they’re used. I have a relationship with the photos so I can and do treat them differently than if they were photos of strangers, but I think I use them in a way that is also as props or objects.

Archives have consistently been a topic of contention and exploration, as also addressed in Noor’s LooseLeaf Curatorial Series “Archival Pulse.” What, in your opinion, makes archives essential for initiating conversations about diaspora identities and experiences, especially within Indigenous, Black, and People of Colour (IBPOC) communities?

I think it comes down to the fact that we don’t often see ourselves included in history books, or at least from our own perspectives. Until recently and often still, IBPOC people and experiences have been written about (or photographed by) outsiders from the community, and their perspectives are often taken more seriously than those who come from a cultural community. I think it’s about taking back those narratives and validating our own voices. It’s a hard balance doing that while staying true to ourselves and not feeling tokenized, but I also think it’s rewarding work.

I’m captivated by the way Veena navigates the intersections of migration, cultural translation, and authenticity, all while incorporating Saris and technology. It’s truly a captivating piece, offering a distinct experience whether viewed as a standalone video or as part of an installation. What role does installation have in your work? How does installation allow you to explore nuances of complicated narratives?

I always felt that I would never be able to say everything I had to say in one photo or one single piece, although I think my ideas around that are changing now. But installation allows me to combine a number of mediums to bring in a more complicated reading of my work. I’m always interested in complicating things and not giving clean answers, but rather asking questions. Sometimes it’s using physical space like the gallery or lately my studio to bring different elements together and indicate all the different things I’m thinking about. Installation allows me to tie different threads together in a single work.

What memorable responses have you received about you work, and have they changed the way you think about making art?

Some good and some critical! Recently I did a TV interview and the reporter asked me what my work was about and what I wanted people to get from it. It was a very direct question that you don’t usually get in the art world, and I appreciated the challenge of answering that for the public and especially for a non-art audience. I think it’s always important to keep the public in mind and not get too caught up in the specifics. I want my work to be complicated but still relatable on a base level to people of all backgrounds and ages.

Also when I was able to show my work in Pakistan in 2016 and received positive feedback on the way I was approaching my subjects and practice, that was very affirming for me. I think a lot of diasporic artists worry if their work will not hold up or still be relevant if they take it back to the audience from the “motherland”. I was definitely worried about this before I went but I was so relieved to find support from local audiences and my extended family. I would encourage all diasporic artists to try and have that experience if they’re able to, because you will learn a lot from it.

What are some themes/questions that you have been pondering about recently?

Recently Amy Wong did a session at Mercer Union with collective EMILIA-AMALIA (of which I am a member) and we were speaking a lot about motherhood or parenthood and the art world. We were speaking mostly about the artist-as-parent relationship and including children in the art world or the decision not to. Afterwards I also started thinking more about the artist-as-child relationship and including our own parents and elders in the art world. Most artists you speak to don’t bring their parents to art activities or say that their parents don’t really understand their career choice.

This past month I was very sick and my parents were taking care of me and as a result coming to a lot of my art activities and events. It was nice because they got a better understanding of what exactly it is that I do and were totally interested and engaged in all of it. A lot of people said to me “it’s so nice that you bring your family to things”, but I’m wondering why this is such an anomaly, especially when so many artists I know make work about or inspired by our families? Why is there a big separation between what is work and what is life, when so often they intersect? I think if we took a little more time and effort to include our families, that gap wouldn’t feel so big.

What’s coming up next for you in your creative career?

I’m looking forward to some of the shows I have coming up, most notably the New Generation Photography Award show at the National Gallery with Luther Konadu and Ethan Murphy. Also I am trying to finish my MFA at Concordia University here in Montreal. I’m looking forward to finishing but being a student has a lot of perks so also a little sad!

Lastly, what does being a “Canadian” artist mean to you? Do you feel that you have a particular responsibility as a second generation who is an artist?

Being a Canadian artist to me simply means that I live and work in so-called Canada, and I also happen to be born here. I think my work responds to this society and things I have encountered while living here. It also means engaging in the history and current politics of the places I engage with. “Canadian” is not a label I shy away from but I am interested in the contexts in which it tends to comes up.

I don’t think I feel a specific responsibility for being a second generation artist, although I used to feel resentful that I felt like I had to talk about migration experience within my work. But I’ve found ways to push back against this while still addressing it at times. I’ve been lucky enough to find a means to express myself through art and found support both from my community and from my family. I am concerned about how my work reads to the larger public, my family, and my cultural community, and I do feel responsible to represent them in a way that is honest and respectful. But ultimately I can only talk about my own experience within my work.

To learn more about Sharlene Bamboat, visit her website.

To view more of Zinnia Naqvi, visit her website.