Originally published on June 8, 2019 on Project 40 Collective’s Blog.

When I reflect on Mimi’s short film SOLACE, a lingering resonance comes to mind. The film’s deliberate lack of sound, aside from the echoes of her father’s prayers, left a profound impact on me. Film has consistently intrigued me as an art form and narrative vehicle—the potential for visuals and sounds to blend, alter, or recede to encapsulate a fragment of thought, dreams, or existence. Mimi’s decision to omit dialogue and music captured a private instance of devotion, permitting the subtlety of silence to resound.

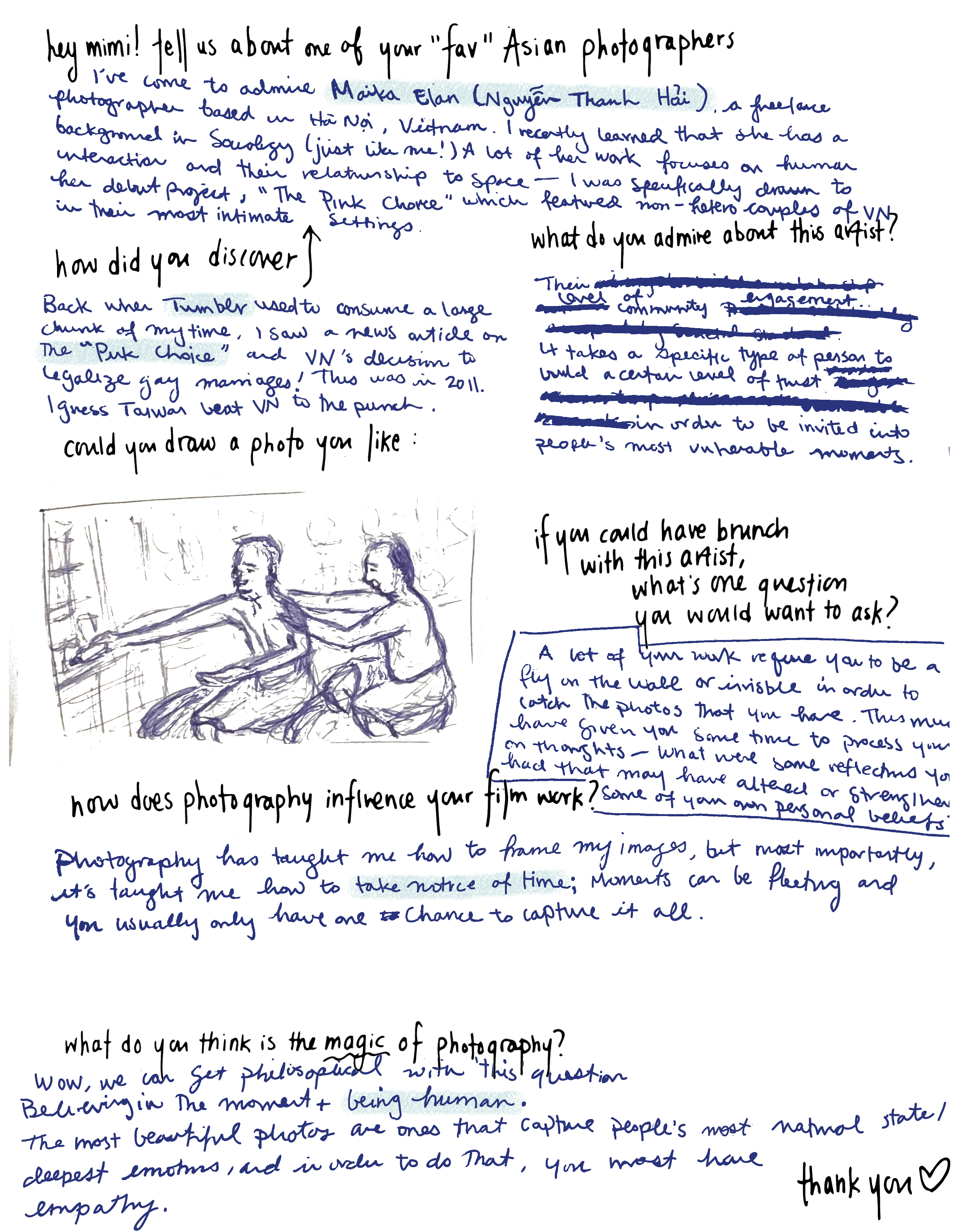

I’m consistently thrilled to encounter individuals who seamlessly blend their social science background with their creative pursuits. As someone with a Sociocultural Anthropological education, I was particularly intrigued by Mimi’s methodology of merging her Sociology knowledge with her creative inclinations. It’s captivating to observe how she approached film and the craft of filmmaking, as well as her interaction with subjects — both individuals and content. Read below to learn what I’m talking about, plus Mimi’s journey into filmmaking and her “favourite” photographer who coincidentally also has a Sociology background.

Tell us briefly about your creative journey! When did you see film and filmmaking as a way of expression?

I never thought that film would be in my bundle of creativity. It was known from a very young age that I had an interest in building things with my hands—and I give my parents credit for this.

I belong to a generation that was raised on television. My parents worked multiple of jobs, which left me home alone for a very long time. I would play with whatever was available: loose leaf grid paper, old phone books, newspaper, pens (we didn’t have a lot of toys to play with). Because I had nothing but time, I had a lot of opportunities to practice drawing, often trying to imitate my favourite cartoon characters (Sailor Moon!) so I could play with them later.

In addition, I sang a lot, and fiddled around with my sister’s electric keyboard when she wasn’t home. (Music became an important element in helping me frame my films, often serving as a great inspiration.) All of these activities were free and accessible to me, so anything involving technology was a big learning curve—and I was ever so impatient. (I swore off photography and filming after my dad made me record him do home activities so we could send them to our family in Vietnam. The footage was less than acceptable, and I was never asked to record anymore family activities ever again.)

However, in high school, I somehow found myself creating promotional videos (or “propaganda” as I use to joke) when I saw a need to connect students with their peers and school. We had a poor reputation among other schools within the city because we were underfunded, which meant we supposedly had fewer shiny programs to brag about. This last part was untrue because we had many extracurricular programs that could build school morale—our problem was that not a lot of students took advantage of these programs because our method of communication (P.A. and printed newsletters) often broke down.

I saw an opportunity to try to take advantage of the fact that we were a technologically advanced generation by showingstudents what their school could be, by filtering information in a fun, accessible, easily consumed, and visually appealing medium. YouTube videos became an obvious solution.

My first project as the Student Council President, Operation Propo: Video.

(Note: I didn’t have any film experience at the time, but I had ideas of what I wanted.

I asked students from the yearbook class and photography club to film for me while I directed.)

I think I was correct to see filmmaking as an effective medium for communication. The returns were high. After establishing our own school’s YouTube channel, I noticed not only the ways in which our student engagement increased, but also how our videos became a buzz, a topic that connected different grades and social groups together. But I can’t say that our videos were the sole reason to our school’s success. Our existing extracurricular programs were already genuinely impressive thanks to the school’s supportive staff. I’ve realized that our videos were just vessels that informed a large group quickly enough to take charge of their own actions.

You can say I’ve taken this little experiment to heart, considering how I’ve tangled myself in film these days.

My favourite propo video, and preceding video.

Videos were also effective way to communicate and address our community’s concerns. Here’s an example.

Much of your body of work delves into the Vietnamese diaspora, frequently intertwined with your personal experiences. Particularly with projects that hold deep personal significance, such as Flagged (2017) and Khoai Lang (2016), where real family archival videos were incorporated, how do you manage the creative process as an individual and as a director?

That’s a good question. When I was working on Flagged, I never seriously considered myself as a “director”. That’s probably because I saw Flagged as academic paper in video form rather than a film, which I often associate as a medium for entertainment.

I started making short videos because I felt like it was a more accessible alternative to share more about about Vancouver’s Vietnamese diaspora, a topic that hasn’t been widely talked about in academia. I pursued the social sciences because I wanted to understand more about the various distinct social trends found in my communities, and translate them over as “facts” to validate my own experiences. But since I only had my own family stories and home videos to fall back on as my primary source, my films quickly became personal projects.

However, I made a conscious effort in my projects to say that while these series of events happened to my family, and are commonly found in other Vietnamese diasporic households, what you see is not the embodiment of the Vietnamese diasporic experience. I learned very later on in my journey of self-reflection that diversity exists within the diasporas, and that recognizing those differences is imperative. We have been hurt by the American media for portraying Vietnamese people in a single narrative, and in turn, we have continued to hurt our own communities by claiming one distinct identity to represent us all—this is what we talk more about in Flagged.

Several themes in your recent films revolve around concepts like “freedom,” “hope,” and “the dream,” but they are all interwoven with underlying truths that add complexity. What is it about the medium of film that empowers you to navigate such intricate terrain? Additionally, does your academic background influence your approach to the craft of filmmaking?

As a Sociology major, I was taught to never make definitive claims about social phenomenons, despite my own experiences and the data that may be collected because social phenomenons are much more complex when they involve multiple parties. We may suggest solutions but not without having observed the situation holistically. This is how I approach filmmaking.

Aside from the fact that film is an accessible and easy way to filter information, I love how film can be open for interpretation. When it comes to addressing more complicated topics that involves multiple parties with varying perspectives, a film can lay out those different perspectives and arguments, but ultimately, the viewer decides what to make of the information that they have received.

I have a deep appreciation for SOLACE (2017), featured in LooseLeaf Vol.5 digital magazine, due to its subtlety and profound impact despite the absence of dialogue or music. It manages to encapsulate a raw moment solely through visual editing. Could you share your experience of working without dialogue in this project? Furthermore, I’m interested in your perspective on the interplay between visuals and sounds within the realm of filmmaking.

I’m so happy and thankful that you enjoyed SOLACE! I’m always surprised to hear positive feedback because this was my first visual heavy film.

Having said this, I had difficulties creating it. SOLACE was an assignment prompt meant to help us practice our camera work (this was an Asian Canadian community engagement documentary class consisting of non-film students). I would not have taken this film approach otherwise. I wasn’t too worried about having a film without dialogue—silent films have music, what else is new? But a film without dialogue AND music? Tough. How do you engage an audience when there’s no dialogue to tell them what to hear, or no music to make them feel? While the brainstorming process was driving me nuts, the idea of my dad’s prayers eventually popped into my head because his prayers would often demand silence from the entire house.

Since film is supposedly a reflection of reality, I think sound and audio are present to ensure that viewers don’t feel disconnected from the film that they’re watching (forgive me for this able-ist approach). We are often afraid of silence because it creates awkward tensions (I’m guilty for speaking too much to fill the gap), and it leaves you alone with your own thoughts. But in Buddhism, you meditate to achieve mindfulness, to allow reflection. I’m not a spiritual person, and so I had a tough time understanding the purpose of silence. In the end, SOLACE is my personal interpretation of what that silent process looked like—to find peace but alone, in cycles but redundant.

Recently, what themes or questions have you been pondering about?

I think since I have created a lot of films about my own diasporic communities, I wonder if I am focusing on this topic too much. There’s always that dilemma as a person of colour on where you draw the line because you don’t want to only be defined by your heritage and ethnicity. But then again, is there real harm if that’s where your interests lie?

What’s coming up next for you in your creative career?

I am taking a break from filmmaking for awhile, but am currently trying to complete a short documentary that a few classmates and I started a year ago. The film focuses on our relationship to home and heritage spaces — we followed a few Chinese Canadian students’ on their journey to visiting their ancestral homes (Sze Yup region) for the very first time.

After that, I may be involved with my alma mater and a local museum in creating a video series focusing on Vancouver’s Chinatown and other diasporic communities (crossing fingers on more Vietnamese and SEA stories). I won’t be handling the filming, but I’ll hopefully be more on the directional and planning process. We will see!

Lastly, what does being a “Canadian” artist mean to you?

Oh. I don’t think there’s a clear answer to this question, but when I hear “Canadian artists”, I think of the Group of Sevens and Shania Twain. Since I can’t relate to any of their art and visually don’t fit into this narrative of what “Canada” paints itself to be, I feel a disconnect with that label: “Canadian” artist. But “Canada” and “Canadianness” is a colonial concept, which means I’m not supposed to fit in this description anyways.

As a second generation in the Vietnamese diaspora performing work in this place called “Canada”, I am a settler, like most people living on this land. In that case, if being “Canadian” means being uninvited, does that make me a “Canadian” artist?

If I were to call myself a “Canadian” artist, it’s less so as a marker for which nationality I pledge my allegiance to, but more so as a descriptor of my own lived experiences. My environment informs how I perceive the world, and as a result, influences the work that I create as an artist.