Originally published on March 12, 2019 on Project 40 Collective’s Blog.

I first encountered Meera’s work in person at CONVENIENCE, an exhibition delving into the “processes of diasporic place-making that take root within spaces stereotypically associated with Asian immigrants.” I vividly recall co-curator Belinda Kwan sharing a video of Meera’s creation: a seemingly ordinary winter coat, transformed into a tapestry of vivid colours, textures, and embellishments. At the exhibition, I witnessed the meticulous craftsmanship and purposeful selection of materials evident in the juxtaposition of contrasting colours and patterns. These elements converged to craft a narrative that captured a facet of an ongoing and evolving experience—whether personal, collective, or encompassing both.

Meera was among the first artists to come to mind when I was planning for the re-launch of Creator to Creator. I hadn’t encountered a significant number of craft-focused works by an Asian. Canadian artist, especially one who already boasted a portfolio in a distinct medium. What truly captivated me about Meera’s art was its symbiotic relationship with aesthetics and purposeful dialogue, presenting unconventional avenues for storytelling, documentation, and the reimagining of the commonplace activity of “dressing.”

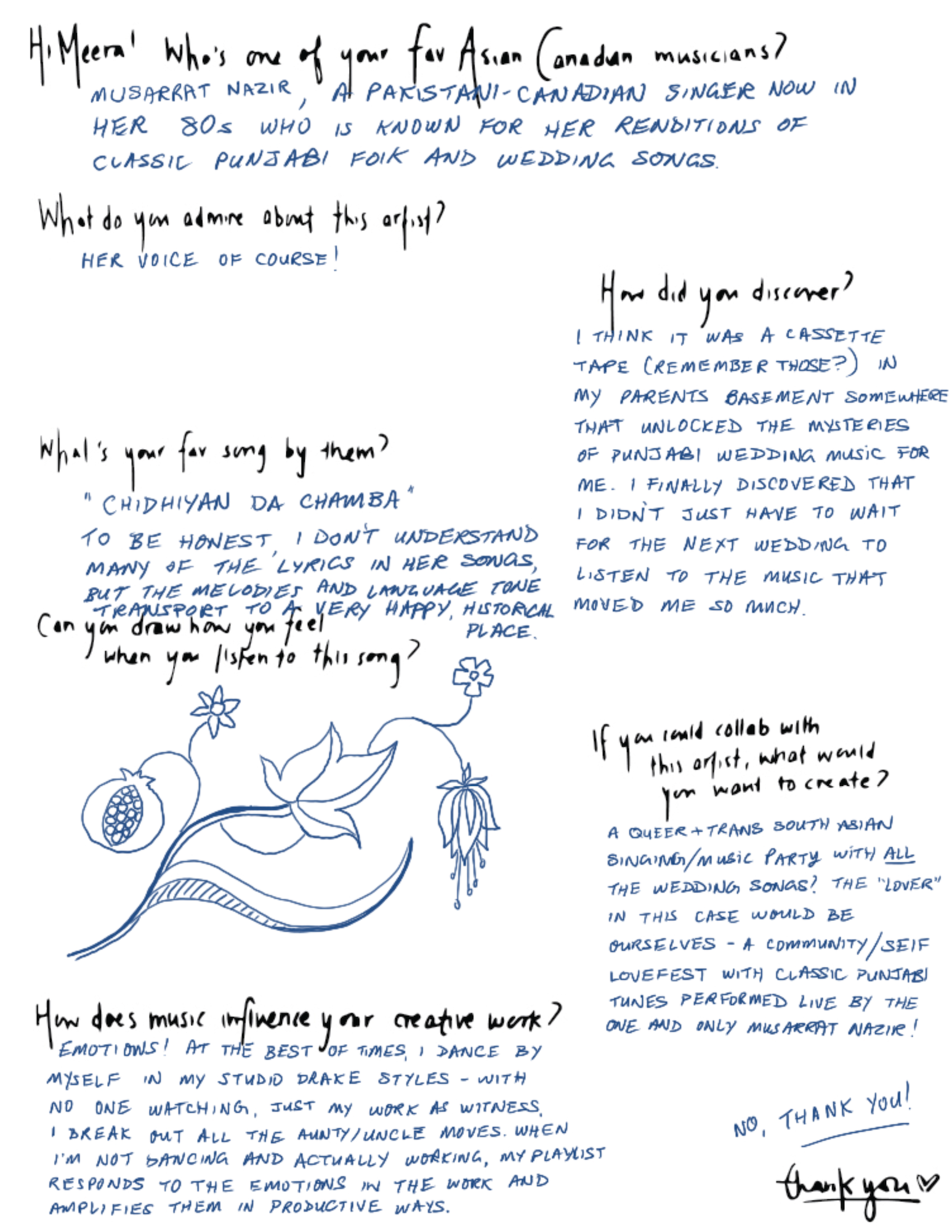

Read below to delve into Meera’s magical moment, her creative process, and the discovery of her “favourite” musician tucked away in her parents’ basement.

Can you briefly tell us about your creative journey? How did your interest in fashion emerge?

In a self-portrait I made while in Grade 1 or so, I drew in detail that plaid dress I was wearing. When I rediscovered this drawing decades later, I was amazed at the early eye I had for clothing.

My creative journey as a professional artist, however, took a few twists and turns. After graduate school in Cultural Theory, I worked as a self-taught freelance graphic designer. After a few years of this, I decided to explore other creative avenues and pick up where I left off as an emerging artist in an undergraduate BFA program at York University in Toronto. As an undergrad, I worked mostly in installation and drawing and had a few shows in Toronto, including a text-based intervention at the old AGO. Later, as an emerging professional artist, I lived in the Abell Lamps Building (now condos) right across from the Drake Hotel and behind Woolfitt’s Art Supplies on Queen Street.

The northern light was absolutely amazing in my place and on a whim, I decided to purchase some liquid acrylics and large stonehenge paper to play around with. There must have been some magic in the air because the drawing and colour experiments I made in those days became artworks that led me down an entirely new path. I had begun a series of paintings on paper I titled Firangi Rang Barangi that explored hybridity in clothing from a contemporary diasporic South Asian perspective. The work did exceptionally well with the entire series selling out between Canada and India, including being invited to show a work at my dream store at the time — Bombay Electric — in Mumbai.

From Begum to Sariscape, your work revolves closely around and involves the body, whether through the subject, the material or in the craft. How much of yourself become a part of your work, and your work a part of you?

It’s only very recently that I would describe my work as being about the body. Like many women, queers and POCs, I remained distanced and disassociated from my actual body while making work that figuratively “dressed” the body. That process of moving from an external locus of investigation to an internal, body-aware one has been fascinating to me in my work. In Firangi Rang Barangi, Upping the Aunty and Begum, I articulated an interest in sites of fashion that have been marginalized or less explored – as an observer, looking in. In more recent work, like Outerwhere, I find that I am drawn to stories more rooted in and expressed through the felt body, like memory, trauma, and healing – a kind of looking out. Both expressions are equally interesting to me and equally define my work. Both are actually about the body, how it feels, what it hides, what it shares, and how it does this. And all of it begins with me. I always begin with an intuitive sense of what to make. This sense is closely aligned with my own life concerns and intellectual processes

I’m utterly enamoured with your Outerwhere series. The act of disrupting the purpose, value, and historical context of clothing, while weaving in a narrative of migration and colonialism, strikes me as an act of de/colonization in itself, in parallel with the artwork it produces. Do you share this perspective? Can you elaborate on the effort invested in bringing your artwork to life?

Outerwhere is dear to my heart. It is a complex, on-going exploration of place, belonging, self, forced and voluntary migration, and of course de/colonization. If there is any one item of clothing that newcomers to Canada must own in order to assimilate and survive, it is a winter coat. It is the most ubiquitous garment of the “Canadian experience”. This one item that maintains appearances of external protection also carries and other, more private stories. These narratives are of all kinds, as diverse as the people who embody the coats.

Still, there are shared elements of leaving familiarity, hiding trauma, struggling to assimilate, uprooting from land, carrying colonial wounding, shattering from racism, negotiating nostalgia, etc. And further, these stories from experiences “back home” intersect with experiences in a “new land”, from one ancient and previously colonized landscape to another ancient and currently colonized one. The parallels, non-equivalencies of these migration journeys are only beginning to be thought through from an immigrant/settler/diasporic perspective. Outerwhere adds to this conversation.

As far as labour is concerned, there are various forms wrapped up into the fibres of the project: emotional, from feeling into the stories; intellectual, from reading about dispossession of Indigenous land in India and Canada to Partition and its colonial and patriarchal violences; physical, from hand-sewing all elements and learning new fibre techniques like felting and embroidery; spiritual, from communicating with the works to intend for them to support healing journeys.

In your artwork, I perceive clothing as holding a significant responsibility, particularly as a means of expression to communicate, articulate, revisit histories, and convey experiences of the South Asian diaspora in North America/Canada. What significance does clothing hold for you within this context?

Clothing is and has always been a significant point of interest and identity-formation for me. I grew up very much as an outsider in public school and high school, ostracized and rejected. Clothing functioned as my support system. I used clothing to express a sense of pride in my non-conforming self. I changed styles as regularly as I changed clothes and found a voice for my body without realizing that I had one. I scavenged and shopped, in Canada and in India. It gave me a focus and an external tool with which to shape my emerging identities layered with my memories and histories. I hope to make clothes one day as well.

Where do you get your fashion inspiration?

I look a lot to contemporary Indian fashion and friends in the industry. I also look a great deal at “street style”, the everyday people I pass by at home or while traveling. I also look to the communities I feel a part of for inspiration. In terms of what I wear personally, I go through phases where I love the loud and colourful and times when I prefer the minimal and subdued. I almost always feel my best self in loose Indian clothing and natural fibre – clothes I can’t wear here in Canada too often!

Lately, what questions have you been contemplating?

How are our small, individual personalities shaped by the large, intergenerational political traumas (colonialism, Partition, caste violences, racism, white supremacy, patriarchy, etc) over which we have little control? How can we be more compassionate towards some of our confounding coping mechanisms by seeing them as responses to the bigger picture?

What can we look forward to, in your creative career, in the next few months?

A stepping back into photography with an upcoming residency in Banff led by Deanna Bowen and Brendan Fernandes, and a continuation of the Outerwhere series. Oh, and the launch of a new series of prints called Yoga: A Sartorial Guide exploring alternative dress dreams in yoga culture.

Lastly, what does being a “Canadian” artist mean to you?

What do I mean to “Canadian” art?

Have a listen to Meera’s favourite song by Musarrat Nazir here.

To see her full portfolio: Website / IG @meerasethi